Four Seasons in Japan

Japan has four distinct seasons, called shiki (四季): spring, summer, autumn, and winter. Each season changes not only the weather and scenery, but also our cultural observances. Spring starts with warmth and blossoms. Summer becomes lively with many activities. After the heat, autumn brings harvest and colored leaves. Winter comes with cold winds and quiet reflection. These seasonal rhythms create the background of Japanese annual events.

To understand Japanese customs and observances, it helps to know two things:

- the calendar system (solar and lunar), and

- Nijyu-shisekki (二十四節気, the 24 seasonal divides).

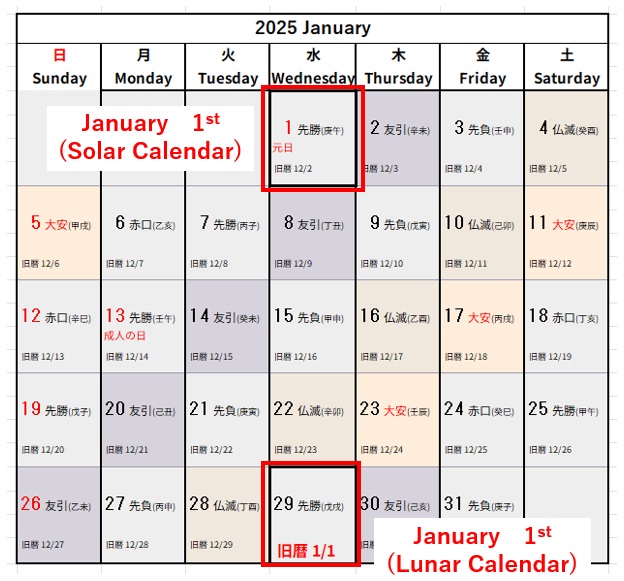

Solar Calendar and Lunar Calendar

In Japan today we mainly use the solar calendar. However, some traditional events follow the lunar calendar because of historical customs. Lunar dates are usually about one month later than solar dates (it can vary by year). When you visit local festivals, please check which calendar they follow.

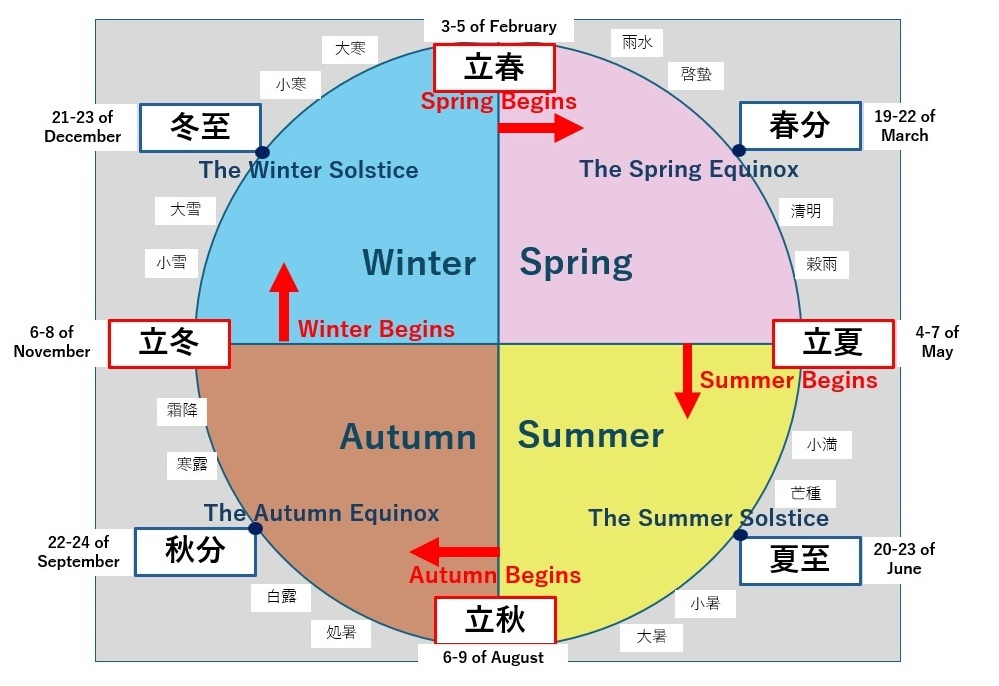

Nijyu-shisekki (24 Seasonal Divides)

This is an old system from China that divides one year into 24 seasonal points. It has strongly influenced Japanese life and agriculture, and still helps describe the feeling of each season.

Eight key points of Nijyu-shisekki (24 Seasonal Divides) :

- Risshun (立春) – start of spring: around Feb 3–5

- Shunbun (春分) – spring equinox: around Mar 19–22

- Rikka (立夏) – start of summer: around May 4–7

- Geshi (夏至) – summer solstice: around Jun 20–23

- Risshuu (立秋) – start of autumn: around Aug 6–9

- Shuubun (秋分) – autumn equinox: around Sep 22–24

- Rittou (立冬) – start of winter: around Nov 6–9

- Touji (冬至) – winter solstice: around Dec 21–23

Spring (January–March)

On January 1, many Japanese use the word of “Shin-shun” (新春, New Spring) as New Year in the new year card, saying “新春のお慶びを申し上げます” meaning “Happy New Year”, and visit Buddhist temples or Shinto shrines for Hatsu-moude (初詣:First Visit), to pray for their health and good fortune in the year.

Setsubun (節分) ,is the day before Risshun(立春- February 3 ,4 or 5 ). At temples and in homes, people do Mame-maki (豆まき, throwing roasted soybeans) to drive away evil and invite good luck.

wearing Heian-aristocratic Kimono

On March 3, families celebrate Hina-matsuri (ひな祭り, Girls’ Festival) by displaying traditional dolls in kimono. Around the spring equinox (Shunbun), we have Higan (彼岸): people visit family graves and remember ancestors.

In late March, Sakura (cherry blossoms) begin to bloom. This timing often matches school graduation ceremonies, and the soft pink flowers seem to celebrate the students.

Summer (April–June)

April is the start of the school year and the fiscal year. Schools hold enrollment ceremonies, and companies welcome new employees with an initiation ceremony.

On April 8, temples celebrate Bussho-e / Hana-matsuri (仏生会・花まつり), the Buddha’s birthday.

On May 5, we celebrate Kodomo-no-hi (こどもの日, Children’s Day). Families with boys often display a samurai helmet or doll, and fly Koi-nobori (carp streamers), wishing for healthy growth and courage.

From late May or June, the Tsuyu (梅雨, rainy season) begins in many regions. “Plum rain” is the literal meaning, because plums ripen in this period. After Tsuyu ends, true summer arrives.

Autumn (July–September)

On July 7, we have Tanabata (七夕). People write wishes on small papers and hang them on bamboo. In some regions, Tanabata is held in August according to the lunar calendar.

Hiroshima Peace Park

Around July 13–16 (or in August in many regions), families observe Obon (お盆 / 盂蘭盆会). They return to their hometowns (Furusato) and visit graves to honor ancestors.

August is also a month to think about peace in Japan. Aug 6 (Hiroshima) and Aug 9 (Nagasaki) are the anniversaries of the atomic bombings, and Aug 15 is the day Japan ended participation in World War II. Many people watch programs and attend memorial events to pray for peace.

Around the autumn equinox (Shuubun), we again have Higan in September, visiting graves and remembering ancestors.

Winter (October–December)

The second Monday of October is Sports Day. Local communities, schools, and companies organize sports and health activities.

From late October to early December, mountains turn red and gold with Koyo (紅葉, autumn leaves). Like Sakura in spring, Koyo is a symbol of Japanese seasonal beauty.

On November 15, families celebrate Shichi-Go-San (七五三, ages seven–five–three). Parents take children to shrines or temples, pray for healthy growth, and often dress them in kimono.

In December, on Touji (冬至, winter solstice), some temples of esoteric Buddhism hold Hoshi-kuyo (星供養), prayers for health and protection.

Christmas has become a popular winter event with lights and cakes, enjoyed by families and couples.

On December 31 (O-misoka, 大晦日), people clean the house (O-soji) to welcome the new year in a pure condition, and prepare for Hatsu-moude. Many also listen to temple bells at midnight.

Summary

Japanese annual events are closely connected to nature, family, and ancestors. We pray for safety and good health, give thanks for harvest and daily life, and strengthen ties with neighbors and relatives. Through these observances, we try to live gently with people around us and with the environment where we live.

Overview of Anual Events and Details of Other Seasons

Please find the details of events in each seasons at following posts.

- Spring in Japan: January to March – Festivals and Traditions

- Summer in Japan: April to June – Traditions and Observances

- Autumn in Japan: July to September – Traditions and Memories

- Winter in Japan: October–December – Traditions and Celebrations

In separate seasonal articles, I will introduce each event in more detail (history, meaning, and how to experience it).

Share Your Thoughts

Have you experienced something similar in your own culture?

Your reflections are welcome.

💬 Jump to the comment section

Share Your Experience of Japan