literally means “monks run,”

reflecting how even the calmest

figures become busy in December.

In Japan, there are many unique customs, as I have introduced in other posts on this blog.

Especially in December, the last month of the year, we have many observances that reflect the Japanese spirit and way of thinking.

We call December “師走 (Shiwasu)”, which literally means “teachers run.” Here, “師 (shi)” refers to Buddhist monks, and “走 (hashiru)” means “to run.” It describes the scene of monks, who usually stay calm in temples, hurrying around to visit their followers’ homes to offer prayers for their ancestors.Even monks are busy at this time, so ordinary people are also busy finishing many things before the end of the year. For Japanese people, the end of the year feels like a kind of “deadline,” when everything must be completed before welcoming the new year.

In Western countries, December is often filled with joyful and festive excitement for Christmas—what we call uki-uki (うきうき) in Japanese. In contrast, Japanese people bustle around in a seka-seka (せかせか) manner—restlessly completing work and cleaning homes.

Why are we so “seka-seka” in December? The answer lies in our traditional sense of time and impermanence.

“Fushime (節目)” – A Milestone in Time

is deeply woven into Japanese

thought and aesthetics.

In Japan, we call the turning points of seasons or the year fushime (節目), meaning a milestone.

We always pay attention to these moments of change.

In my previous post about autumn leaves (紅葉, Kōyō), I introduced the Japanese idea of “無常観 (Mujōkan)”—the awareness of impermanence:

Japan is blessed with four seasons, and with each change we are reminded that time passes and nothing remains the same.

Even the most beautiful scenery must eventually fade.

Knowing this, we try not to cling to sorrow, but instead to cherish the fleeting beauty of each moment.

This sense of impermanence—Mujōkan—is deeply rooted in Buddhism and has shaped Japanese aesthetics.

This concept is beautifully expressed in the opening lines of The Tale of the Heike (平家物語):

The sound of the bell at Gion Temple echoes the impermanence of all things.

The color of the sala trees’ blossoms reveals that the prosperous must decline.

The proud do not last long—like a dream on a spring night.

only once and should be cherished.

Sen no Rikyū, who perfected the Japanese tea ceremony, also taught the idea of “一期一会 (Ichigo Ichie)”—“The time when you (guest) and I (host) meet will never return. Because it is only once in our lives, we should treasure this moment.”

Following this sense of Mujōkan, we believe that “this year will never return.”

Therefore, we try to complete all remaining matters before the year ends, so that we can greet the new year with a fresh and pure mind.

Many Japanese year-end customs reflect this way of thinking.

Praying for Ancestors in December

As mentioned above, Buddhist monks used to visit the homes of their parishioners in December to chant sutras for their ancestors. This custom of year-end ancestor prayers was as common as Higan-kuyō in March and September or Bon-kuyō in July or August.

During the Edo period, when agriculture was the main industry, December came just after the busy harvest season. Farmers visited graves to thank their ancestors for a good harvest and prayed for happiness in the coming year. Cleaning graves before welcoming the new year also became a part of this custom. Even today, although temple rituals for ancestors are less common, many Japanese still visit and clean their family graves in December.

(You can learn more about Bon-kuyō in my previous post: Obon – Praying for Ancestors)

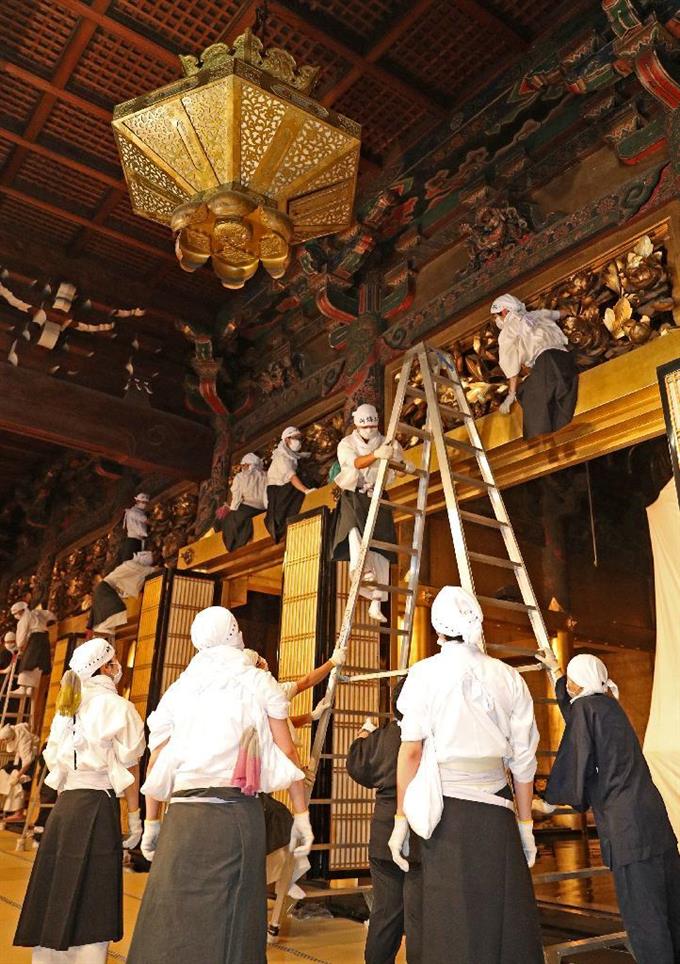

“Susu-harai (煤払い)” – Cleaning at Temples and Shrines

a year-end cleaning to purify

sacred spaces before the New Year.

The custom of cleaning graves among ordinary people is believed to have originated from “Susu-harai”—the great year-end cleaning of temples and shrines. During Susu-harai, statues of Buddha and the buildings are cleaned to purify the sacred space before welcoming the new year. Historical records show that Susu-harai was already practiced in the Heian period (9th–13th century). It was a ritual originally performed by the aristocracy, influenced by ancestor worship and the Chinese calendar system.

If you visit temples or shrines in December, you may see monks or priests cleaning Buddha statues and temple buildings with special tools. Many temples conduct Susu-harai on December 13th, following the tradition of the Edo period, when the Tokugawa shogunate cleaned Edo Castle on that day. Famous examples include Higashi Honganji and Nishi Honganji in Kyoto, and Narita-san Shinshōji in Chiba. At Sensō-ji in Asakusa, Tokyo, Susu-harai is held late at night on December 12th and a special prayer is offered the next morning.

“Ōsōji (大掃除)” – Great Cleaning in Homes and Offices

The Susu-harai ritual of temples and shrines spread to ordinary people as Ōsōji, or “Great Cleaning.”

It has become a very common custom in Japanese homes and workplaces.

As I mentioned in my post Clean Streets, Clean Shops, and Clean Japan, Japanese people have a long tradition of cleaning their surroundings, both physically and spiritually. At the end of the year, we do thorough cleaning to welcome the new year with purity and freshness.

In December, people often ask each other, “When are you doing your Ōsōji this year?”—almost like a seasonal greeting. Stores and companies also start promoting cleaning products in commercials during this time. So, if you visit Japan in December, you may see Ōsōji scenes everywhere—from homes to offices and temples.

“Tōji (冬至)” – The Winter Solstice

Tōji, the Winter Solstice, is the day when the sun reaches its lowest position and daylight is shortest in the Northern Hemisphere. In 2025, it will fall on December 22nd.

a fragrant Yuzu bath to refresh body and spirit.

On this day, many Japanese take a Yuzu bath (柚子湯, Yuzu-yu)—bathing with floating aromatic citrons. This custom has a practical side: the scent and components of yuzu are believed to promote blood circulation and prevent dry skin. Interestingly, Tōji (冬至) and Tōji (湯治)—which means “hot-spring cure”—sound the same in Japanese. This wordplay may have encouraged the custom of taking Yuzu-yu baths on this day. Many hot spring resorts serve Yuzu-yu to guests, and even snow monkeys in Jigokudani Yaen Kōen in Nagano are known to enjoy soaking in it!

“Bōnenkai (忘年会)” – Year-End Party

“forget-the-yearparty,”

marks the joyful closure

of one chapter.

The word Bōnenkai literally means “a gathering to forget the year.” It is a party to forget the troubles and hardships of the past year and to welcome the new year with renewed energy. Though not religious, it reflects the Japanese sense of closing one chapter and starting a new one. Companies, friends, and families hold Bōnenkai to celebrate together.

Want to join a Japanese-style Bōnenkai yourself? Some travel programs and cultural experiences offer guided Bōnenkai or izakaya tours where you can celebrate just like locals.

👉 Join a Japanese izakaya or year-end party experience

“Shigoto-osame (仕事納め)” – Finishing Work for the Year

The Tokyo Stock Exchange

Because Japanese people value Fushime—the milestones of life—many offices and organizations mark the end of December as a time to close their work formally. The Tokyo Stock Exchange holds its final trading day, called “Dai-nōkai (大納会)”, on December 30th. After the speech, participants perform a unique rhythmic handclap called “Sanbon-jime (three sets of ceremonial clapping),” a Japanese custom of three rounds of rhythmic hand clapping performed to celebrate the close of an event and a express gratitude and hope for the coming year. (Please see the actual scene here: after the speech:1:28)

Many companies also hold a final meeting on the last workday of the year, where the president gives a short speech of appreciation and encouragement.

Sometimes, these events are followed by a small Bōnenkai party.

“Joya-no-Kane (除夜の鐘)” – The Bell on New Year’s Eve

The last ritual of the year is Joya-no-Kane, the ringing of temple bells on New Year’s Eve.

Across Japan, Buddhist temples ring their bells 108 times—107 before midnight and once more just after midnight. According to Buddhist belief, humans have 108 earthly desires. By hearing the sound of the bell, people are purified of these desires and can greet the new year with a pure heart.

This custom originated in Zen temples in China during the Song dynasty and was introduced to Japan by the monk Dōgen in the 13th century. By the Muromachi period (14th–16th century), it had become a widespread year-end tradition.

Summary

When December comes, Japanese people start to think, “The year is almost over.” We hurry to finish our remaining work, clean our homes, visit graves, attend Bōnenkai, and prepare for the new year.

Because we value the Fushime—the milestones of life—we want to welcome the new year with a pure and refreshed heart.

The time we have now will never return, so we should treasure each moment we live. This is the essence of the Japanese sense of Mujōkan—impermanence.

If you visit Japan in December, I recommend watching the seka-seka (せかせか) movement of Japanese people. Through that scene, you may feel the quiet beauty of Mujōkan reflected in their hearts.

Next in This Series

As the temple bells ring in the New Year, Japanese people greet January 1st with a pure heart. In my next article, I will introduce how we celebrate the New Year—from Hatsumōde (the first shrine visit) to Osechi (New Year’s dishes) and other early-January traditions.

Please visit my next article “January 1st and the Beginning of the Year “.

Share Your Experience of Japan