What is “Yaku-Doshi” (厄年)?

In Japan, there is a traditional belief called “Yaku-Doshi”, which refers to specific ages in a person’s life that are thought to bring bad luck or misfortune. The word “厄 (Yaku)” means misfortune or troubles, and “年 (Doshi)” means year. These unlucky years are believed to come at certain ages for both men and women.

When Do Yaku-Doshi Years Occur?

Yaku-Doshi ages occur at specific intervals in life. According to tradition:

- For men, the critical ages are 25, 42, and 61.

- For women, they are 19, 33, and 37.

These are counted using a traditional system called Kazoe-Doshi, where a newborn baby is already considered one year old at birth, and becomes two on the next New Year’s Day.

The year before and after the main Yaku-Doshi year are also considered sensitive and are called Mae-Yaku (前厄) and Ato-Yaku (後厄), respectively. Among them, age 42 for men and 33 for women are known as “Tai-Yaku” (大厄), or Great Misfortune Years, and are considered the most dangerous.

The Meaning of “Yaku-Yoke” (厄除)

To avoid the misfortunes of Yaku-Doshi, people pray for “Yaku-Yoke”, which means warding off bad luck. The word “Yoke (除け)” means to ward off, avoid, or protect against. So “Yaku-Yoke” literally means avoiding or eliminating misfortunes.

How Japanese People Avoid Bad Luck

Right after the New Year bells ring, many Japanese visit Buddhist temples or Shinto shrines in a custom called “Hatsu-Moude” (初詣), the first shrine or temple visit of the year. Those who are in their Yaku-Doshi year often:

- Participate in prayer rituals (祈祷, Kito) for protection.

- Purchase protective charms (お守り, Omamori) for Yaku-Yoke.

This custom is so widely practiced that Yaku-Doshi charts are displayed at most temples and shrines. Visitors can check if their age falls into a Yaku-Doshi year.

Historical Background

The origin of Yaku-Doshi is not entirely clear, but it has a long history. One of the earliest references appears in a Buddhist scripture called “Bussetsu Kanjo Bosatsu-kyo”, which mentions unlucky ages such as 7, 13, 33, and so on. The concept also appears in “The Tale of Genji” (Genji Monogatari) written in the 11th century.

By the Edo period (17th–19th century), the belief had spread to the common people, as the use of calendars became widespread. Since then, Yaku-Doshi and Yaku-Yoke have been deeply rooted in Japanese tradition.

How to Know Your Yaku-Doshi: The Kazoe-Doshi System

In the Kazoe-Doshi (数え年) system:

A person is considered 1 year old at birth.

On the next New Year’s Day, they become 2 years old, regardless of their actual birthday.

So, if someone is born on December 31, they are already 2 years old on January 1 of the next year. Using this system, Yaku-Doshi years are calculated.

What You Can Do During Yaku-Doshi

🛐 Prayer Service (祈祷, Kito)

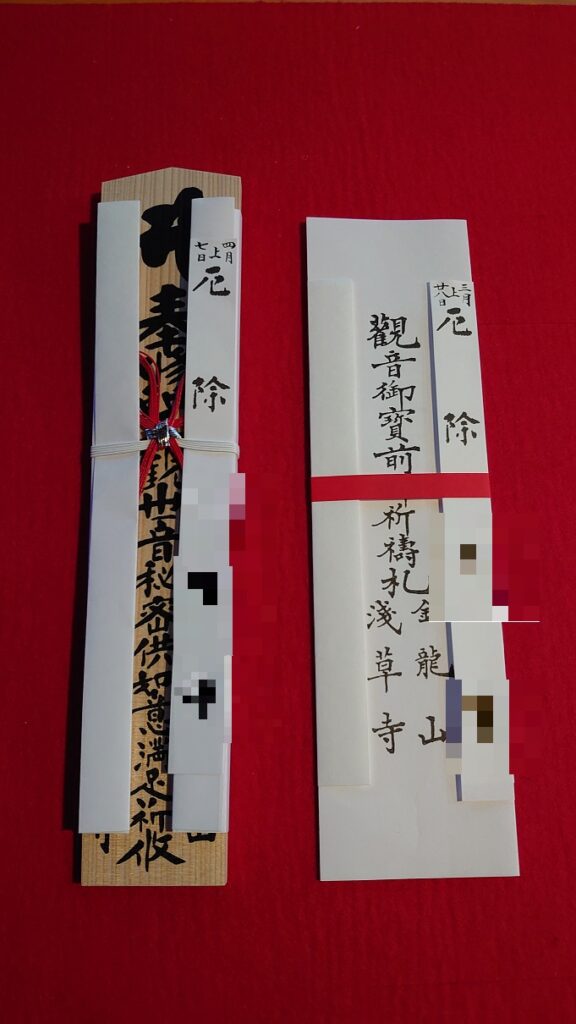

To protect themselves from misfortune, people often visit temples or shrines and receive a prayer service for Yaku-Yoke. A monk or priest conducts a ritual where they pray for your safety throughout the year. After the ceremony, you usually receive a talisman (お札, ofuda) to place in your home.

The cost of such services is usually around 5,000 yen or more.

You can read more in the article: “KITO祈祷 – Prayer Services at Buddhist Temples in Japan.”

🎐 Protective Charm (お守り, Omamori)

If a formal ritual feels too religious or costly, many people opt to carry a small charm called Omamori (お守り) for protection. These charms are popular among Japanese people, and there are versions not only for Yaku-Yoke, but also for traffic safety, exam success, love, and more.

Conclusion: Tradition Still Alive Today

Although many Japanese people today say they don’t follow any specific religion, customs like Yaku-Doshi and Yaku-Yoke show how deeply spirituality is woven into everyday life. Even in modern Japan, people still visit temples or shrines when facing difficult times or uncertain futures.

If you visit Japan in the New Year, check the Yaku-Doshi chart and see if it’s your unlucky year—you might want to get a charm, just in case!

Share Your Thoughts

Have you experienced something similar in your own culture?

Your reflections are welcome.

💬 Jump to the comment section

Share Your Experience of Japan