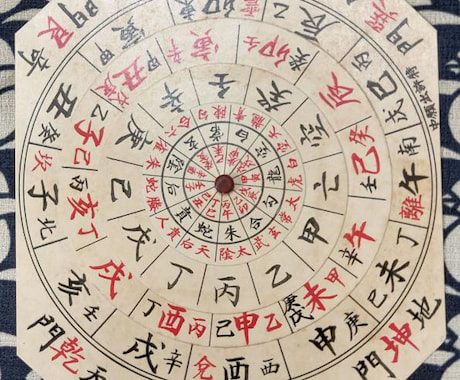

Rokuyō (六曜), a traditional Japanese calendar system

When Japanese people plan festive occasions such as weddings, store openings, or other important events, they often check whether the chosen day is considered lucky. The most auspicious day is called Tai-an (大安)—literally “Great Peace,” known as the day when everything goes well.

Tai-an is one of six days known collectively as Rokuyō (六曜), a traditional Japanese calendar system that indicates whether a day is lucky or unlucky. The six days repeat in a continuous cycle based on the lunar calendar: Senshō (先勝), Tomobiki (友引), Senbu (先負), Butsumetsu (仏滅), Taian (大安), and Shakkō (赤口). Each has its own meaning and level of auspiciousness.

Here’s a quick overview:

- 先勝 (Senshō) – Good luck if you act early in the day.

- 友引 (Tomobiki) – Neutral; avoid funerals because it’s said to “pull friends along.”

- 先負 (Senbu) – Avoid rushing; better luck comes in the afternoon.

- 仏滅 (Butsumetsu) – The most unlucky day, meaning “the death of Buddha.”

- 大安 (Taian) – The luckiest day when all goes well.

- 赤口 (Shakkō) – Unlucky except between 11 a.m. and 1 p.m.

The Origin and History of Rokuyō

Rokuyō has its roots in ancient Chinese divination from the Tang dynasty (7th century). Originally, it was used to determine lucky or unlucky hours of the day, but by the Qing dynasty (17th century), the system evolved to indicate days.

Rokuyō was introduced to Japan around the Edo period (17th–18th century). Books from 1696 and 1747 already contained the same six terms used today, showing that the system was fully established by that time and became popular among ordinary people.

After the Meiji Restoration, when Japan adopted the solar calendar, the government banned the use of divinatory systems like Rokuyō. However, public resistance was strong, and the practice quietly continued. Ironically, this prohibition only made Rokuyō more familiar and widespread in modern Japan.

How Japanese Use Rokuyō Today

the luckiest day, for their wedding ceremonies

Even in today’s society, many Japanese people still consult Rokuyō when planning events such as weddings, funerals, store openings, or even buying lottery tickets.

- On Taian, people schedule weddings or celebrations.

- On Tomobiki, funerals are avoided.

- On Butsumetsu, few people hold joyful ceremonies, while some find it suitable for funerals as it symbolizes “cutting off misfortune.”

Although most Japanese do not consider themselves religious, the influence of unseen forces—Buddha, the gods, or fate—still shapes cultural behavior. This reflects the spirit of engi (縁起), the Buddhist concept that all things arise from interconnected causes and conditions. To many Japanese, choosing an auspicious day simply feels like respecting those invisible connections.

“Ataru mo Hakke, Ataranu mo Hakke” – Divination May or May Not Be True

There is a well-known Japanese saying: “Ataru mo hakke, ataranu mo hakke” (当たるも八卦、当たらぬも八卦), meaning “Fortune-telling may come true, or it may not.”

Even though people know that Rokuyō divination is not always accurate, many still check it—just in case. After all, it never hurts to have luck on your side.

Featured (eyecatch) image courtesy of Santai Jinja (産泰神社)

Share Your Experience of Japan