Year-end Mood make Japanese hold “Bo-Nen-Kai”

As the year draws to a close in November and December, people in Western countries get excited about Thanksgiving and Christmas. In Japan, however, the season feels quite different. People focus on wrapping up unfinished work, cleaning their homes, and preparing for the New Year—what we call “年末気分 (Nen-matsu Kibun / Year-end mood).”

And when this atmosphere begins, the same question starts appearing everywhere:

“When are we having our Bo-Nen-Kai this year?”

In my own case, an ex-colleague called me early this November to decide our date. Eventually, we settled on an early-December dinner at a fugu (blowfish) restaurant. Thanks to this custom, we can meet friends we don’t often see—former classmates, old coworkers, teammates—at least once a year.

For many Japanese people, Bo-Nen-Kai is even more familiar than a Christmas party, which tends to be enjoyed mainly by young couples and families.

What Is Bo-Nen-Kai?

The word Bo-Nen-Kai (忘年会) consists of three characters:

- 忘 Bou – forget

- 年 Nen – year

- 会 Kai – gathering / party

So it literally means “a party to forget the year.”

At the end of the year—considered a “節目 (Fushime)”, or turning point—we look back on what happened, let go of negative moments, and prepare to welcome the coming year with a refreshed mindset.

Fushime and the Japanese Sense of Impermanence

Hard nodes of a bamboo stalk

Originally, Fushime referred to the hard nodes of a bamboo stalk dividing its segments. Over time, the word came to mean a milestone in the flow of time.

This idea connects deeply with a Japanese Buddhist concept called 無常観 (Mujō-kan / Impermanence)—the belief that everything is constantly changing and nothing stays the same.

This worldview encourages us to think:

“The year is ending, a new year is coming. Let’s forget the bad moments and reset ourselves.”

Bo-Nen-Kai reflects this mindset.

The Emergence and History of Bo-Nen-Kai

Unlike many Japanese rituals rooted in Buddhism or Shinto, Bo-Nen-Kai does not appear to originate from religious practice. It seems to have grown naturally from everyday life.

gathering on December 21, 1430

Early Records in the 15th Century

One early reference appears in Kanmon Nikki, a diary written by a prince of the imperial family. The entry dated December 21, 1430 describes a lively gathering after a renga (linked-verse) poetry session—suggesting that sake-filled year-end parties already existed among aristocrats in the 15th century.

Edo Period – Growth Among Merchants

During the peaceful Edo period (17th century), merchants became more active, and year-end gatherings with sake among fellow merchants gained popularity. These gatherings likely included conversations about the many events of the year—including complaints about the Tokugawa government, I guess.

Meiji Period – Spread Among the General Public

In the 19th century (Meiji era), year-end bonuses began appearing for government officials and company employees. This temporarily “rich” feeling led to more extravagant Bo-Nen-Kai events.

Authors and haiku poets also held their own Bo-Nen-Kai to discuss literature and their creative efforts. Natsume Sōseki even mentioned such gatherings in his famous novel “I Am a Cat.”

By this era, the custom had spread widely among ordinary people.

Bo-Nen-Kai in Modern Japan

Today, Bo-Nen-Kai is held all over Japan throughout December. From late November, employees, club members, and neighborhood groups begin discussing:

- When to hold it

- Where to reserve

- What kind of menu or course to choose

Restaurants, izakaya, and banquet halls become the busiest they are all year, so early reservations are essential.

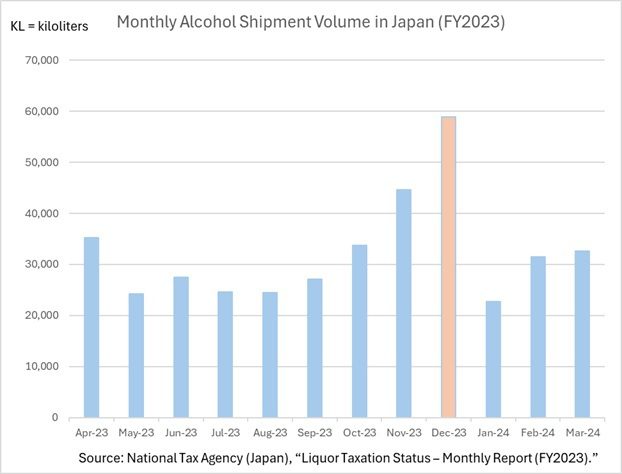

This trend is reflected in Japan’s alcohol shipment data. According to the National Tax Agency, shipments peak sharply in December—clearly showing the impact of the Bo-Nen-Kai season.

Summary

If you visit Japan in December and dine at an izakaya or a restaurant with small banquet rooms, you may encounter a lively Bo-Nen-Kai.

These gatherings help us forget the year’s troubles and welcome the new year with a fresh heart—an idea rooted in Mujō-kan (impermanence) and our awareness of moving from one “Fushime” to the next.

Modern Bo-Nen-Kai may simply look like cheerful parties with food, drink, and conversation. Yet at the end, you can often hear a message like:

“Thank you for your hard work this year. Let’s have an even better year ahead.”

The evening ends with 三本締め (Sanbon-jime), a rhythmic ceremonial clapping that symbolizes closure and marks the transition to the coming year.(Please see the actual scene here: after the speech:1:28)

Experience Japan’s Izakaya Culture for Yourself

If reading about Bonenkai made you curious about Japanese drinking culture, you can experience it in a fun and easy way by joining a local izakaya tour. Explore Japanese food, sake, and nightlife with a knowledgeable guide.

👉 Join an Izakaya Tour in Tokyo

If you’re planning to visit Tokyo this winter, staying in popular nightlife districts makes it easy to enjoy Japan’s izakaya culture.

Share Your Experience of Japan